Dan Trueman

Four Squared For Ligeti

Immediately before Four Squared for Ligeti was Justice Partial, a piece commissioned by the Kalamazoo Laptop Orchestra (KLOrk, of course). David Code, KLOrk’s director, suggested I work with the two disklaviers they have there, and mentioned in passing that, should I be interested, they can be tuned up in various ways (David got the pianos as part of a fascinating adaptive tuning project he has worked on for many years, the Groven piano).

Should I be interested?

Needless to say, I was, and I ended up with a pair of tunings, one a basically conventional just-intonation, the other a tuning based more on overtones. I called the tunings “just” and “partial,” hence the title of that piece, which I will write about some other time, when it is recorded. More about these tunings, and the origins of the partial-tuning in fiddle music, can be found in the score for Four Squared.

Of course the cool thing about disklaviers is that they can play themselves, or, really, be played automatically given the proper digital messages. So, again for Justice Partial, I bound the disklaviers together via a little program I wrote where the notes played on one disklavier (say, the just-tuned disklavier) would set a metronome of sorts (regularly repeating notes) going on the other disklavier (in this case, the partial-tuned disklavier). For example: our just-pianist plays a C-major chord on the just-tuned piano (and it is a funky sounding C-major, since this particular just-tuning is rooted at A, not C) and immediately the partial-tuned piano begins repeating a C-major chord (tuned funky in a different way) at a given tempo. Thus provoked, the partial-pianist might respond with a low F#-octave, which would in turn trigger the just-piano to begin its own metronome on those low F#s. The fun begins.

This same odd pairing of pianos is also at the core of Four Squared for Ligeti, except in this case my pianos are digital—all in software—instead of actual disklaviers, mostly for practical purposes (I don’t have two disklaviers, and it’d be a pain to gig this piece if it requires them)—and I call them synchronic pianos. Sandwiched between these two misfits is… an actual, old-fashioned piano, played by the wonderful Kathy Supové, who I had been talking with for quite some time about a piece for her and laptop orchestra.

So, what do we have so far?

Piano soloist and the synchronic pianists, or “side pianists” as we sometimes call them. This trio forms the core of the ensemble for Four Squared. Here’s a picture of the premiere, with Kathy and the Princeton Laptop Orchestra:

So who are all those other people, and what are they doing? Well, there is me, standing next to Kathy, breaking a sweat conducting. Then there are those who look like they might be doing Tai Chi (badly, I suppose, though they played the piece great!), which gets us into two other sections of this orchestra. The first section, which I call the Stretched-Pianists, is playing piano samples with the now ubiquitous “tether.” Using a phase-vocoder based instrument that I built (called the Sound Marionette), the players are able to “freeze-frame” through the piano samples, sustaining them indefinitely, playing slowly (or quickly) backwards and forwards through them, and also retuning them in ways similar to the partial and just pianists.

Each of these players is paired with one of the side-pianists over the network, and the pitches of their pianos change according to what the side-pianists play. Their parts are notated conventionally, and when there are accents, they are meant to draw across the attack of the piano samples, sometimes getting a backwards piano attack (when they draw the tethers up/out) and other times getting a normal (though perhaps fast or slow) piano attack when they release the tethers down/in. By the way, this is the same instrument that I used in neither Anvil nor Pulley for So Percussion, and you can watch a nifty little video they made about it. The very opening of Four Squared features the stretched-pianists slowly pulling backwards through piano samples, peaking on the first downbeat of the piece.

The second instrumental section, also appearing to be involved in a yoga practice of sorts, is using the tether to play a completely different instrument: the blotar. You can learn more about this instrument in this paper, but basically it’s a synthesis algorithm that models both the flute and the electric guitar (strange though it may be, the physical models for these two instruments are almost identical!) that can range from delicate, breathy pitched tones through squealing feedback-like sounds, all performed with a tether. I put Rebecca Fiebrink’s wonderful Wekinator to work creating a neural-network link between the tether and synthesis algorithm, all via a novel use of machine learning that Rebecca has been developing. The tether-blotars make their first appearance—quietly, to start—at right around the four-minute mark in Four Squared.

Then there are those other laptopists sitting with, of all things, laptops… in their laps. And they are typing! This particular instrument was inspired by Ge Wang’s CliX instrument, and it makes lovely clear little semi-pitched clinking-glass-like sounds (listen at round 3:30 in Four Squared for their first appearance, and then they go a bit mad for a spell at around 5:20 in). I should add that in more recent performances of Four Squared I have replaced the typists with actual percussionists; it’s a long story, but in the end I only want to use laptop-based instruments if they truly get us somewhere that conventional instruments can’t, and in this particular case I’ve found conventional percussion to be much easier and a lot cooler for this particular section of the orchestra; all part of the learning process.

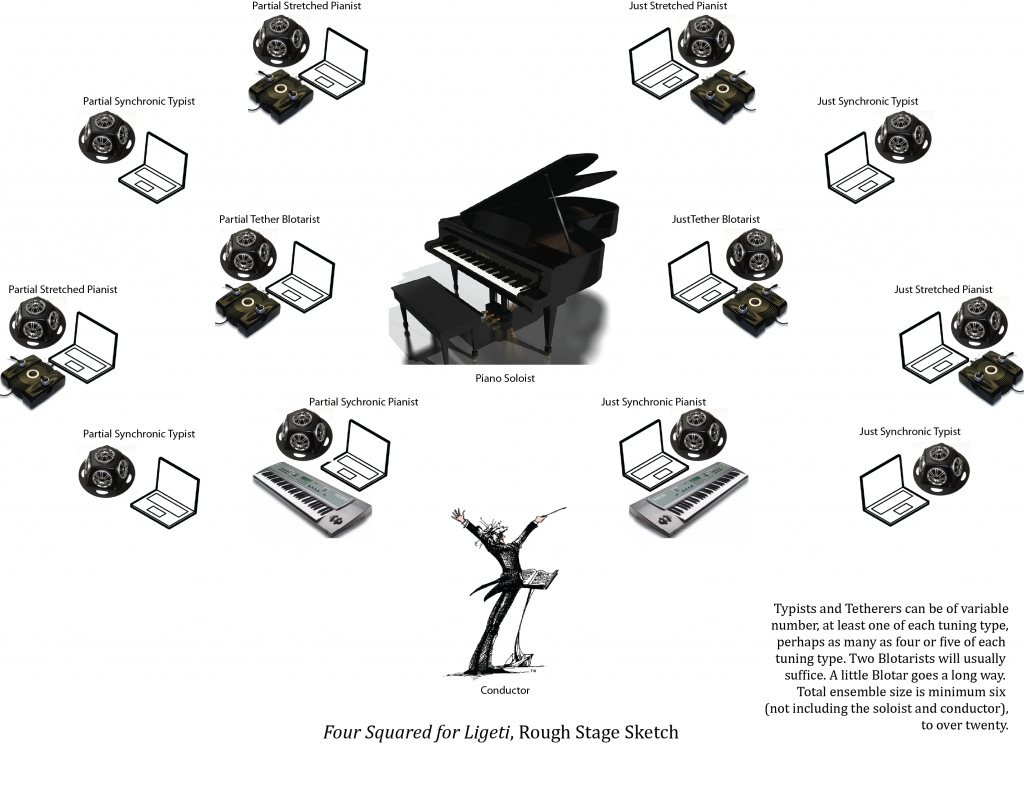

So, that’s the orchestra for Four Squared:

Well, almost. There is also a big bass drum (or a not-so-big bass drum, if a big one isn’t available) that makes an appearance towards then end of the piece, and as many old fashioned mechanical metronomes as we can muster, which we let loose at maximum tempo, also shortly before the end of the piece, and they quickly start phasing; this is the most obvious explanation for the reference to Ligeti in the title. But, anyone familiar with the film Eyes Wide Shut will recognize hints of the haunting and beautiful Musica Ricercata II, which Ligeti wrote in the 1950’s and which still sounds tautly contemporary. But, what about the Four Squared in the title?

I wrote Four for myself on 6-string electric violin back in the mid-1990s—have a listen:

I don’t play 6-string anymore, and while I made a version for cello, it is super hard, and I like the piece well enough that I wanted to try to find a new home for it. This didn’t quite turn out that way, in the sense that Four is meditative and spacious while Four Squared is noisy and cluttered, but the notes themselves are the same; Four almost reads like an analytical reduction of Four Squared. And it is squared in that the loose, breath-driven phrasing of Four becomes regimented and boxed in by the metronomic insistency of the synchronic pianos in Four Squared.

Now, at this point if there is an intrepid ensemble out there that wants to give this piece a go, I am sure there are a few questions. Here is what would be required:

- a really good pianist.

- two MIDI-keyboards and laptops (Mac OSX), with software that I can provide; this is standalone software that runs with a double-click.

- 4+ other laptops, for the stretched-pianists and the tether-blotarists (the typists have been replaced by two percussionists); again, I’ve written the software for all of these, and it is standalone and runs with a double-click.

- two percussionists, playing a small setup (two ceramic mugs and two slats of wood); these replace the typists of the original version.

- tethers would be great. They aren’t impossible to come by and are easy to hack. But, it is also possible to remap the software with a different interface, so lack of tether is not a non-starter.

- a wireless router that all the laptops connect to, using Jascha Narveson’s LANdini software (also standalone).

- speakers near each player. Of course, we prefer the hemispheres, but there are lots of other possibilities, so not having them shouldn’t be a non-starter either.

- as many old fashioned mechanical metronomes as can be mustered; we do it with about 14.

- a conductor, though I suppose it might be possible to do without; Sideband has yet to try.

- lots of perseverance to get things off the ground and learn to play together in this truly unusual way.

Take a look at the score if you are not yet frightened away, and contact me (manyarrowsmusic [at] gmail [dot] com) if you want to explore the possibility further. And here is a picture of Sideband in one of our rehearsals of Four Squared for Ligeti; I have to say it is great fun to play!